Remember the Mozart Effect?

Turns out that the media made a mountain out of a molehill. Playing any type of music the listener enjoys gives a temporary bump in cognitive abilities. But playing Mozart through the nursery iPod or headphones placed strategically above your occupied uterus does not turn your child into, well…Mozart. Or Baby Einstein, for that matter.

Well-meaning arts teachers, desperate to avoid the axe, and loving parents, hopeful of their child’s future college opportunities, and avaricious companies, eager to make a buck, all sprung into action. See? Classical music makes your child smarter.

Lost in all of this, I believe, is a real soul-searching conversation with ourselves about what it means to be a successful parent, not to mention a whole and fulfilled person.

But there is no easy answer to those questions and no quick fix for those challenges. We’d much rather have flashcards and DVDs or expensive designer playgrounds that provide the solution.

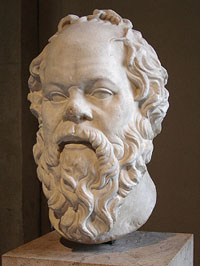

I want my children not just to listen to Mozart in the hope that they will have high test scores but to love Mozart because the music will give them access to infinite realms of beauty that I believe make life worth living.

Play or Practice Makes Perfect?

The latest controversy centers around play. Once again, admission to most-selective colleges is set as the goal.

In the CNN article, “Want to get your kids into college? Let them play,” a former preschool teacher and director and a professor, both currently serving as “Masters” of a residential house at Harvard, explain how play breeds success:

But academic achievement in college requires readiness skills that transcend mere book learning. It requires the ability to engage actively with people and ideas. In short, it requires a deep connection with the world.

A similar article in the New York Times has been making the rounds among my friends, fellow bloggers, and even some of my favorite toy companies on facebook. The Movement to Restore Children’s Play Gains Momentum” is more subtle in its discussion of the academic payoff to play but still mentions future academic success as part of the reason to promote play.

Amy Chua, Yale law professor, author, and parent, strikes back with the idea that Chinese Mothers are Superior. The actually not-at-all misleading subtitle explains the premise: “Can a regimen of no playdates, no TV, no computer games and hours of music practice create happy kids?”

Chua describes forcing her daughter, age 7, to practice a piano piece until she gets it right:

Back at the piano, Lulu made me pay. She punched, thrashed and kicked. She grabbed the music score and tore it to shreds. I taped the score back together and encased it in a plastic shield so that it could never be destroyed again. Then I hauled Lulu’s dollhouse to the car and told her I’d donate it to the Salvation Army piece by piece if she didn’t have “The Little White Donkey” perfect by the next day. When Lulu said, “I thought you were going to the Salvation Army, why are you still here?” I threatened her with no lunch, no dinner, no Christmas or Hanukkah presents, no birthday parties for two, three, four years. When she still kept playing it wrong, I told her she was purposely working herself into a frenzy because she was secretly afraid she couldn’t do it. I told her to stop being lazy, cowardly, self-indulgent and pathetic.

The proponents of play come off as infinitely more sympathetic than Chua.

And I completely agree that play is an integral part of childhood. And, yes, play does allow children to practice creative problem solving, engage in cooperation, and develop empathy. Not to mention the body and mind connection…mens sana in corpore sano.

And yet, in spite of some cringe-worthy anecdotes and stereotypes, Chua does have some valid points to make. Hidden within her martinet’s description of her routine with her young daughters is the wisdom that not all of knowledge is to be found in unstructured play:

- “Tenacious practice, practice, practice is crucial for excellence…”

- “Rote repetition is underrated in America.”

- “But as a parent, one of the worst things you can do for your child’s self-esteem is to let them give up. On the flip side, there’s nothing better for building confidence than learning you can do something you thought you couldn’t.”

And there is joy, of course, in achieving excellence.

A Middle Way

Reading these two articles, one might think there is no middle ground. However, young children can learn persistence and gain the satisfaction of achieving mastery in self-directed play.

Pushing a very young child into academics before she is ready will usually backfire. Stereotypes of Chinese-American parenting should not be confused with education in China but they do bear some strong pedagogical similarities. Teacher Tom, an innovative preschool educator, blogs about the pitfalls of the Chinese government’s model of education.

Fortunately, the Chinese model is not the only successful one. Finland has some of the highest academic achievement measures in Europe and yet students start at age 7 and spend relatively fewer hours in school. Delaying formal instruction until a child is ready may mean the child is eager to learn and will achieves more rapid success in acquiring academic skills.

The High Price of (Early) Success

I worry about children forced to bloom at an early age. No doubt they have impressive achievements very young and make “spiky” (vs. well-rounded) college admissions candidates. Incessant training in preparation for a clear goal will ready a child for that test or performance…but for little less.

Writing an A+ essay is one thing, the creative drive to craft a work of insightful fiction is another entirely. Acing a science test may get your foot in the door but developing a life-saving medical procedure requires a flexibility of mind and an innovative way of approaching a problem.

Memorizing the answers of others will only get you so far in finding your own solutions.

Burnout is another real risk of early achievement. Children who function on the auto-pilot of external motivation may suddenly find themselves adrift as they become more independent young adults.

There are prodigies who are miserable, who snap, or who simply walk away from the activity that was supposed to give them joy.

The how of success loses meaning without the why.

A Well-Examined Life

And yet, a musical prodigy will not come to play at Carnegie Hall spending his youth noodling around on the keyboard until he loses interest.

At the risk of fence-sitting, perhaps there is a season for all things.

When I was a young musician, myself, I noticed that practicing produced technical accuracy but that true brilliance came from an inner spark of creativity that was not teachable. Without technical accuracy, however, the soul is without foundation. Without soul, the skill cannot soar.

There are practical issues raised by these articles. As a parent, I worry that my four year old daughter’s interests and talents lead me to over-schedule her. I carefully preserve and guard her free time even as she asks for more classes, more crafts, more piano practice, more reading. And I also look to the future and wonder, when she inevitably hits a wall, when something gets tough or she experimentally asks if she can “quit”, how do I know if she really wants to quit or if she really wants a little push.

Before we “lose the forest for the trees”, maybe we can take a step back.

What is the purpose of understanding music if it does not increase your enjoyment? Do you work hard only for laurels? What good is a lot of financial success if you are not sure what you want to buy?

I took a great deal from my experiences at Yale and Harvard but is admission to a selective university the end goal of a life?

If the goal is to graduate from an Ivy League university, with a perfect average, no less, or play at Carnegie Hall, what about the 99%, or more, of people who will not achieve these goals? Even among my classmates, only a handful will be the best–the soloists, the Nobel and Pulitzer winners, the CEOs, the Presidents and Supreme Court Justices. Are we setting children up for disillusionment when we create such literal measures for success?

What is it that makes a life worth living, anyway?

And what tools does a child need to build that sort of life for herself?

So, I encourage my kids to go out and play because that’s the sort of parent I want to be and that’s the type of family I want to have…not because I think it will make them smarter or get them into a better college or earn them a higher paying job.

@kimtracyprince Just posted on this topic, juxtaposed w the “play” articles: http://www.naturallyeducational.com/2011…

@candaceapril Great approach Candace! http://www.naturallyeducational.com/2011…

Great post and I love how you presented these views. We’re big fans of free play here, but we don’t let the kids walk all over us either. I do appreciate how Amy Chua said in her interview on the Today Show that often times parents can see the full potential of their children even if they can’t see it.

I remember reading somewhere that violinist Itzhak Perlman practiced far less than his peers – and that, while that may be why his technical excellence is sometimes questioned, he remains popular because of his ability to play with genuine soul. And I would love, love, love to see an interview with Amy Chua’s daugthers someday!

I see early childhood especially as a time for play – and a time where, if you don’t let them play, the opportunity can be lost forever.

Really good article!

Thomas goes on to say, “You can try to have the same scheme. But what separates us is our intellect and our personnel. The biggest reason for our success is that we hold each other accountable for every little detail.

[…] relationships with other bloggers. Check out this extremely well-written trackback tutorial Permalink […]